Demystifying the Monty Hall Problem: A Step-by-Step Guide

The Monty Hall problem is a famous probability puzzle that has been the subject of many debates and controversies. In this post, we’ll explore the problem and its solution in a simple and accessible way for all audiences.

Monty Hall Problem

Suppose you’re on a game show, and you’re given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what’s behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, “Do you want to pick door No. 2?”

The host, naturally, knows in advance which of the three doors hides the car. This means that whatever door you initially choose, he will always open another door with a goat behind it. The question is: Would you stick with your original choice, or would you switch? Is it to your advantage to switch your choice?

The instinctive, but incorrect, answer of almost all newcomers to the problem is: “Stay, since it is equally likely that the car is behind either of the two closed doors”. In this post, we’ll see why this answer is wrong, and we will gain a strong understanding of why switching is the best strategy.

Probability Review

Before we delve into the Monty Hall problem, let’s review some fundamental concepts of probability.

Sample Space and Events

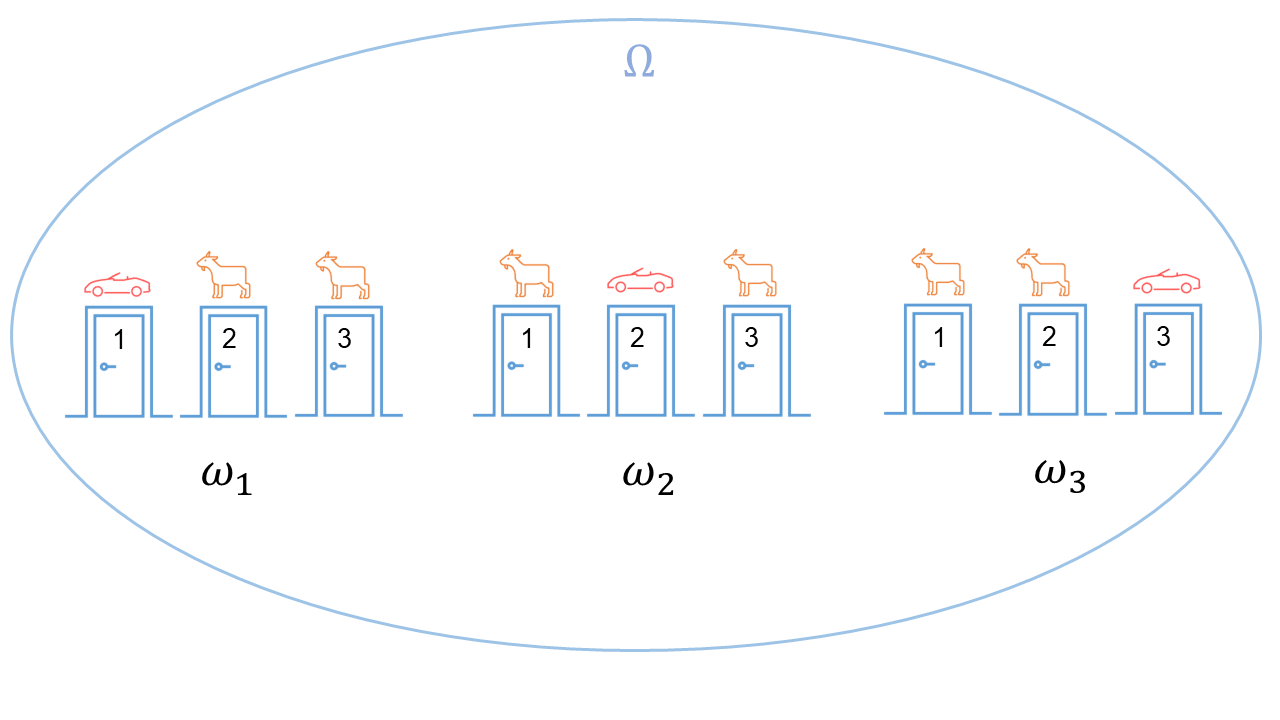

Imagine a set of $N$ possible outcomes, denoted as \(\Omega = \{\omega_1, \omega_2, \dots, \omega_N\}\). Each outcome $\omega_i$ represents a possible result of an experiment. For instance, in the context of the Monty Hall game, $\omega_1$ might correspond to the car being behind door 1, $\omega_2$ to the car being behind door 2, and $\omega_3$ to the car being behind door 3. This collection of outcomes is called the sample space \(\Omega = \{\omega_1, \omega_2, \omega_3\}\).

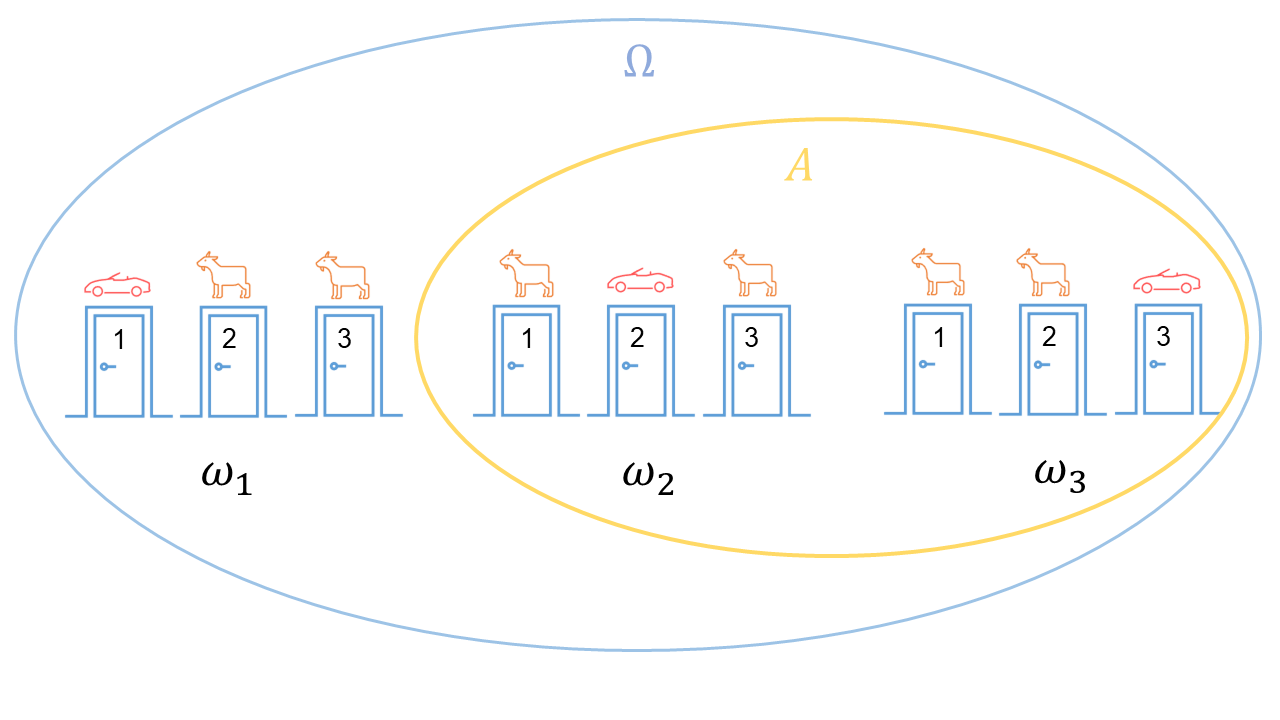

An event $A$ is a subset of the sample space, i.e., $A \subset \Omega$. For instance, let $A$ be the event where the car is not behind door 1. Then, \(A = \{\omega_2, \omega_3\}\).

The probability of an event $A$ is defined as the ratio of the number of outcomes in event $A$ to the total number of outcomes in the sample space $\Omega$:

\[\mathbb{P}\{A\} = \frac{\text{number of outcomes in } A}{\text{total number of outcomes}}\]In the previous example where $A$ is the event where the car is not behind door 1, the probability of $A$ is \(\mathbb{P}\{A\} = \frac{2}{3}\), as there are two outcomes in $A$ and three outcomes in $\Omega$.

The given definition is valid only if all outcomes are equally likely to occur. This is the case in the Monty Hall problem, as we assume that the car is equally likely to be behind any of the three doors.

Conditional Probability

Frequently the probability we want to know is conditional on some event. The effect of the condition is to remove some of the events in the sample space, or equivalently to confine the admissable items of the sample space to a limited region. Continuing with the previous example, let $A$ be the event where the car is not behind door 1, and $B$ the event where the car is not behind door 3.

The probability of $A$ given $B$ is the probability of the car not being in door 1 given that we already know that the car is not behind door 3. In other words, we are restricting the sample space to the outcomes in $B$. We can think of this as removing the outcomes that are not in $B$ from the sample space $\Omega$.

Now we get a new restricted sample space $\Omega’$ and a new event $A’$. The probability of $A$ given $B$ is the probability of $A’$ in the new sample space $\Omega’$:

\[\mathbb{P}\{A'\} = \frac{\text{number of outcomes in } A'}{\text{total number of outcomes in } \Omega'}\]Note that $A’$ is basically the intersection of $A$ and $B$, and $\Omega’$ is simply $B$. Therefore, the probability of $A$ given $B$ can be written as:

\[\mathbb{P}\{A \mid B\} = \frac{\text{number of outcomes in } A \cap B}{\text{total number of outcomes in } B} = \frac{1}{2}\]Solving the Monty Hall Problem

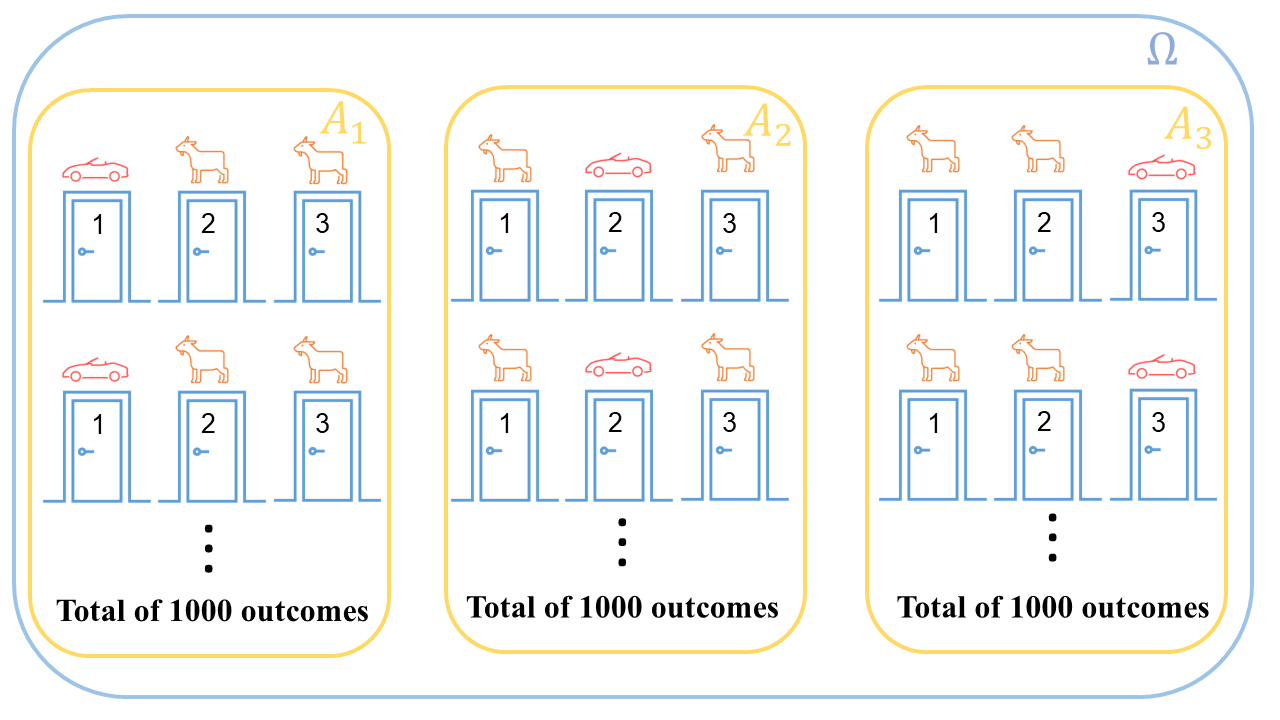

To solve the Monty Hall problem, we consider playing $3000$ games of the Monty Hall game. Each game is an experiment, in which the car is randomly placed behind one of the three doors. We assume that the car is equally likely to be behind any of the three doors, so we expect to have approximately $1000$ outcomes with the car behind door 1, $1000$ outcomes with the car behind door 2, and $1000$ outcomes with the car behind door 3.

Then, our sample space $\Omega$ is the set of all possible outcomes of the $3000$ games. The event $A_1$, $A_2$, and $A_3$ is defined as the event where the car is behind door 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Lastly, we assume that the door we choose to open is always door 1, as this doesn’t affect the probability of the car being behind any of the doors.

We are now in a position to solve the Monty Hall problem. We’ll consider two approaches: one where the host is ignorant of the doors’ contents, and another where the host is not. Our goal is to compute the probability of winning the car if we stick to our original choice, defined as \(\mathbb{P}\{W\}\).

First approach: An ignorant host

Let’s start by assuming that the host doesn’t know what’s behind the doors. The rules are the same as before. You pick a door, and the host opens one of the remaining doors at random. There are two possible scenarios:

- The host opens a door with the car behind it. In this case, the game would make no sense, and it would be discarded.

- The hosts opens a door with a goat behind it. In this case, you have two doors left: the one you picked and the one the host didn’t open.

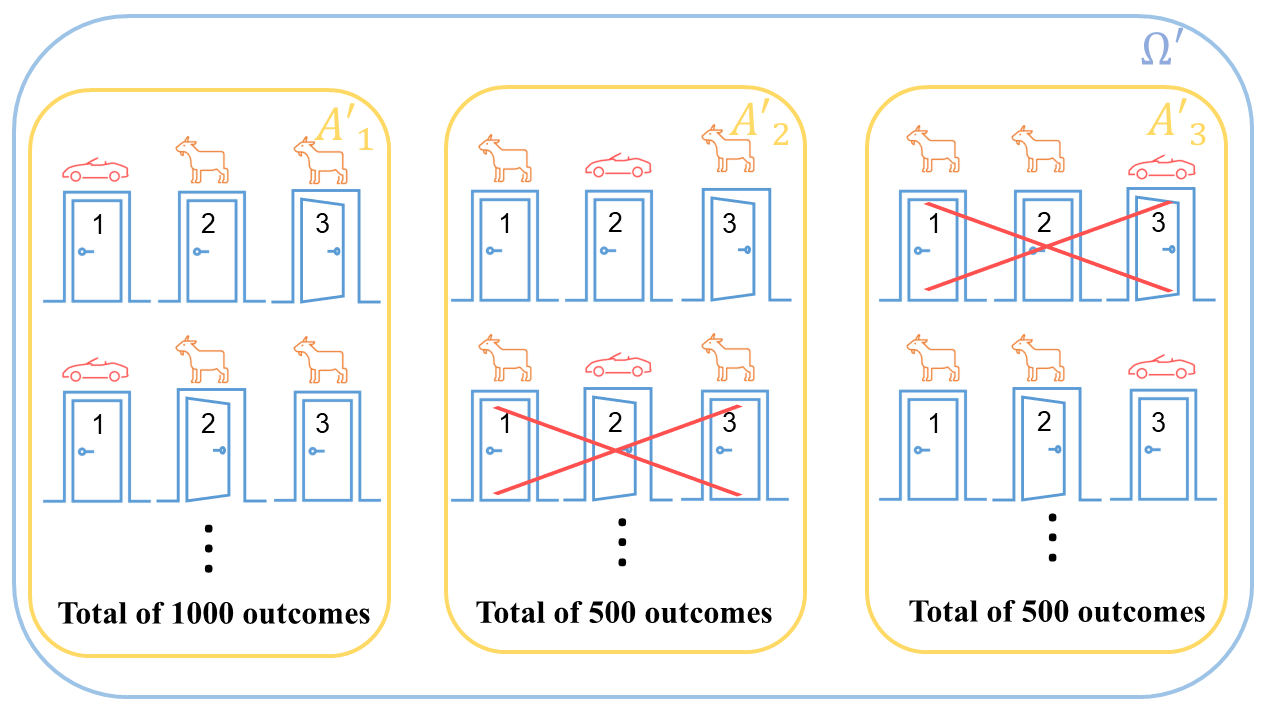

The probability of the host opening a door with the car behind it is $\frac{1}{3}$. That means that we expect one out of three games to be discarded. From the event $A_1$, no outcomes are removed, as the host would never open a door with the car behind it. From the events $A_2$ and $A_3$, half of the outcomes are removed, as the host would open a door with a car behind it half of the time.

We are now left with a restricted sample space $\Omega’$ and a new event $A_1’$, $A_2’$, and $A_3’$. If we decide to keep our initial choice, door 1, we would win only if the observed outcome is in $A_1’$. Otherwise, we would lose, as the remaining outcomes in $A_2’$ and $A_3’$ have a goat behind door 1. Therefore, the probability of winning the car by keeping our initial choice, given that the host doesn’t know what’s behind the doors, is:

\[\mathbb{P}\{W\mid \text{host opens a door at random}\} = \frac{\text{number of outcomes in } A_1'}{\text{total number of outcomes in } \Omega'}\]By replacing:

\[\mathbb{P}\{W\mid \text{host opens a door at random}\} = \frac{1000}{1000 + 500 + 500} = \frac{1}{2}\]By keeping our initial choice, we have a $50\%$ chance of winning the car. This is the same probability we would have if we decided to switch doors. Therefore, it doesn’t matter if we keep our initial choice or switch doors, as the probability of winning the car is the same in both cases.

Second approach: A knowledgeable host

We have now arrived at the most interesting part of the Monty Hall problem. What happens if the host knows what’s behind the doors? Let’s assume that the host knows where the car is, and he always opens a door with a goat behind it. From the event $A_1$, the host would open a door 2 or 3 indistinctly, as both doors have a goat behind them. From the event $A_2$ the host will always open door 3, as door 2 has a car behind it. Evidently, the host will open door 2 for outcomes in event $A_3$.

Because the host never opens a door with a car behind it, there are no discarded games. Therefore the sample space $\Omega’$ is the same as the original sample space $\Omega$. If we decide to keep our initial choice, door 1, we would win only if the observed outcome is in $A_1’$. Otherwise, we would lose, as the remaining outcomes in $A_2’$ and $A_3’$ have a goat behind door 1. Therefore, the probability of winning the car by keeping our initial choice, given that the host knows what’s behind the doors, is:

\[\mathbb{P}\{W\mid \text{host opens a door with a goat behind it}\} = \frac{\text{number of outcomes in } A_1'}{\text{total number of outcomes in } \Omega'}\]That is:

\[\mathbb{P}\{W\mid \text{host opens a door with a goat behind it}\} = \frac{1000}{1000 + 1000 + 1000} = \frac{1}{3}\]We have a $33.3\%$ chance of winning the car if we keep our initial choice. It’s clear that we should switch doors, as the probability of winning the car is higher if we do so.

Conclusion

The Monty Hall problem serves as an intriguing demonstration of how our intuitions about probability can sometimes lead us astray. At first glance, the choice between sticking with the initial door or switching might appear inconsequential, given that there are only three doors involved. However, a deeper analysis reveals that the host’s knowledge about the doors’ contents significantly impacts the probabilities.

When the host’s actions are driven by randomness, as in the case of an ignorant host, the probabilities of winning the car remain evenly distributed. The uncertainty introduced by the host’s choice balances the scales between sticking and switching, resulting in a $\frac{1}{2}$ chance of success for both strategies.

However, the true essence of the Monty Hall problem comes to light when the host is knowledgeable and deliberately reveals a goat. In this scenario, sticking with the initial choice leaves the contestant with a $\frac{1}{3}$ chance of winning, while switching doors increases the likelihood of success to $\frac{2}{3}$. This unexpected outcome challenges our intuitions and emphasizes the importance of considering conditional probabilities in decision-making.

The Monty Hall problem underscores a valuable lesson in probability theory: updating probabilities based on new information is a crucial aspect of making informed decisions. Whether in game shows or real-life situations, understanding how probabilities evolve as circumstances change can lead to more favorable outcomes. So, while the Monty Hall problem might have seemed counterintuitive at first, it serves as a compelling reminder that sometimes, probabilities can be much more intricate than they initially appear.

Bibliography

- Richard W. Hamming - The Art of Probability for Scientists and Engineers.

- Gill, Richard - The Monty Hall Problem. Mathematical Institute, University of Leiden, Netherlands.